Some while ago I read a ‘classic’ of George Mavrodes: Belief in God (1970). In this book he is concerned with epistemological questions with regard to God’s existence. An passage in the beginning of the book attracted my attention. It’s the paragraph about the question ‘How Do You Know?’. That however appears to be an ambiguous question. He illustrates that statement with two examples (p.6,7):

Imagine a girl who has gone to considerable trouble to keep her engagement a secret from everyone except her family and that of her fiancé. She then is disconcerted when a casual acquaintance mentions it. In her surprise she may blurt out “But how do you know?”

Imagine now a second case. A firmly convinced atheist listens patiently as a Christian expresses his faith. Then the atheist replies, “You say there is a God an that he loves you. How do you know?”

Although the same expression (How do you know?) is used, nonetheless different questions have been asked, says Mavrodes. “The most important difference between these two questions is that they are asked against quite different backgrounds with respect to the propositions that is claimed to be known” (p.7). In order to articulate this difference more fully, Mavrodes makes a distinction by calling the first question ‘biographical’ and the second ‘a challenge’.

The first question is called biographical because the ‘you’ in it is to be understood in the personal sense. The question is really about the knowledge of this particular friend, so her reply has to be autobiographical. It’s not the moment to talk about general principles as to how people usually get to know things like this. A second feature of this kind of question is that does not concern the truth of the proposition to which it refers. There is no disagreement about that: the lady has been engaged.

The second type of question (that of the atheist) he calls a ‘challenge’. It might even be argued that it’s not a genuine question at all. In contrast with the biographical question, the personal element in a challenge is lacking or at least not really significant. The possible replacement of ‘you’ by ‘one’ is a good indicator for that. The question is not especially about this particular Christian. “The challenge is issued to him, but it is not about him” (p.8). There is however another difference. “Responses to a challenge may be evaluated in terms of their truth or falsity. But it is also important to evaluate these responses in terms of their effectiveness or success” (p.9). The challenge, in contrast with the biographical question, poses a task. That point suggests another contrast, according to Mavrodes. A relevant response to a biographical question will include saying (or writing) something, a piece of information. “For challenges however”, says Mavrodes, “it’s by no means clear that the most relevant or even the most standard response must be in words. In general we can notice that nonverbal means are often the most effective and the most appropriate for convincing a person of the truth of some proposition” (p.9).

So far for the discussion in Mavrodes’ book. I can tell you that I read it with a considerable amount of surprise. Let me explain. This book was published in 1970, that is to say: definitely long before anything like ‘Postmodernism’ was in the air. One of the influences of postmodernism in recent theology is the emphasis of ‘relevance’, at the cost of ‘truth’ (Alister McGrath for example). My surprise therefore was a double one. In the first place that the emphasis on relevance was already there, in Mavrodes’ book so many years before the talk of Postmodernism. But even more important to me was this: for Mavrodes ‘relevance’ and ‘truth’ are no enemies, but go side by side. That is, according to me, an important insight, worth keeping in mind. The church has to be concerned with the relevance of the message of the Gospel, but also with the truth of it, by explaining and defending it in the best possible way.

I’m happy to announce the publication of my article “‘Naturally More Vehement and Intense’: Vehemence in Calvin’s Sermons on the Lord’s Supper”, in Reformation & Renaissance Review, vol. 20,1 (2018), 70-81. The online (open access!) and printed versions are available at the RRR’s

I’m happy to announce the publication of my article “‘Naturally More Vehement and Intense’: Vehemence in Calvin’s Sermons on the Lord’s Supper”, in Reformation & Renaissance Review, vol. 20,1 (2018), 70-81. The online (open access!) and printed versions are available at the RRR’s  In her book Christ and Horrors. The Coherence of Christology (2006), the late

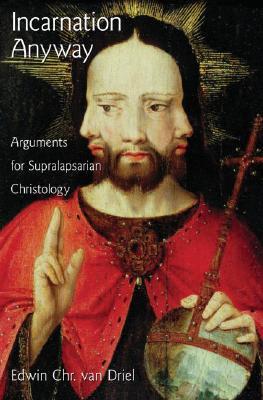

In her book Christ and Horrors. The Coherence of Christology (2006), the late  three arguments for a supralapsarian Christology, in conversation with Schleiermacher, Dorner, and Barth. One of his arguments is the Argument from Divine Friendship. My rendition here does not justice to the richness of his thoughts. However, it will hopefully serve to see the supralapsarian logic at work. ‘Friendship’, Van Driel says, ‘is motivated by a delight in and a love for the other’. Of course, he explains, friendships can be in danger, be under pressure, and so on. Friends, real friends, will look of course for reconciliation. However, that means that the wish for reconciliation is prompted by a deeper motivation: the longing for friendship, for community, for mutual love. That is what is at stake in the Incarnation. God is not merely solving ‘our problem’. His goal is friendship with us. This might sound rather familiar to you. Yet it could lead be translated into a rather different Christmas sermon. To illustrate what I have in mind, I can suffice with pointing to a sermon of Samuel Wells, which offers an eloquent illustration. Wells very convincingly points out that the heart of God’s reaching out for us can not be captured (only) in the word ‘for (God did this for me)’, but rather in the word ‘with’ (God wants to be ‘with us’). If you look for inspiration for your Christmas sermon along these supralapsarian lines, you might watch

three arguments for a supralapsarian Christology, in conversation with Schleiermacher, Dorner, and Barth. One of his arguments is the Argument from Divine Friendship. My rendition here does not justice to the richness of his thoughts. However, it will hopefully serve to see the supralapsarian logic at work. ‘Friendship’, Van Driel says, ‘is motivated by a delight in and a love for the other’. Of course, he explains, friendships can be in danger, be under pressure, and so on. Friends, real friends, will look of course for reconciliation. However, that means that the wish for reconciliation is prompted by a deeper motivation: the longing for friendship, for community, for mutual love. That is what is at stake in the Incarnation. God is not merely solving ‘our problem’. His goal is friendship with us. This might sound rather familiar to you. Yet it could lead be translated into a rather different Christmas sermon. To illustrate what I have in mind, I can suffice with pointing to a sermon of Samuel Wells, which offers an eloquent illustration. Wells very convincingly points out that the heart of God’s reaching out for us can not be captured (only) in the word ‘for (God did this for me)’, but rather in the word ‘with’ (God wants to be ‘with us’). If you look for inspiration for your Christmas sermon along these supralapsarian lines, you might watch

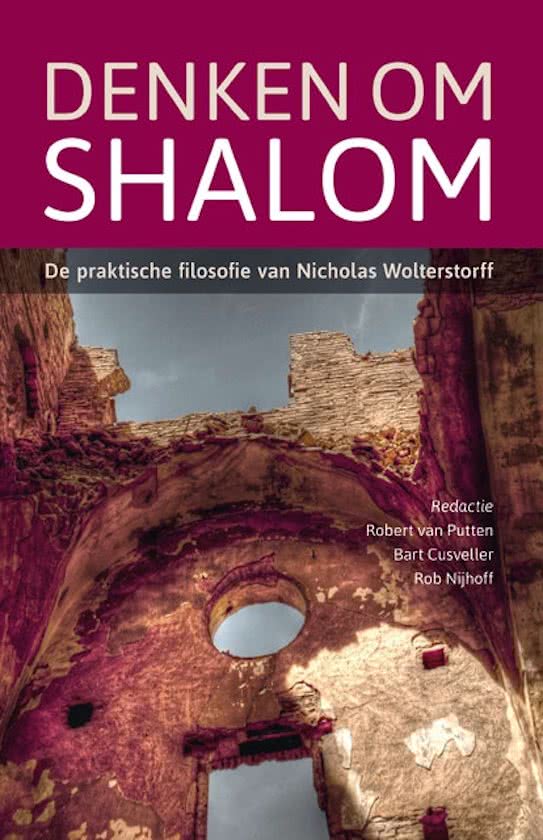

Wolterstorff started his talk with a reference to Jeremiah 29,7: ‘Seek the shalom of the city…’. How does this mandate relate to the present phenomenon of populism? A first important step in Wolterstorff’s analysis was the interpretation of populism in terms of loss. A populist laments the loss of a former way of life, be it the Amercian, Dutch or French way of life. A second step in his analysis is to point out that the populist claims to have a right to (t)his way of life. And if this right is not fulfilled, he considers himself to be a victim. There is – in short – a moral dimension to populism, which is often ignored. So, the question is: is the populist right in his claim? Wolterstorff said: it depends… On what? There is no serious moral reflection or the beginning of an answer yet. That at least was Wolterstorff’s conclusion.

Wolterstorff started his talk with a reference to Jeremiah 29,7: ‘Seek the shalom of the city…’. How does this mandate relate to the present phenomenon of populism? A first important step in Wolterstorff’s analysis was the interpretation of populism in terms of loss. A populist laments the loss of a former way of life, be it the Amercian, Dutch or French way of life. A second step in his analysis is to point out that the populist claims to have a right to (t)his way of life. And if this right is not fulfilled, he considers himself to be a victim. There is – in short – a moral dimension to populism, which is often ignored. So, the question is: is the populist right in his claim? Wolterstorff said: it depends… On what? There is no serious moral reflection or the beginning of an answer yet. That at least was Wolterstorff’s conclusion. 80’s. I am not sure they would have passed the test of shalom at that very moment. The process of reconciliation in South Africa was hard and it took many years, while never been fully completed. Yet, Wolterstorff considered their fight to be just, in contrast to the present fight of populism. Why is that?

80’s. I am not sure they would have passed the test of shalom at that very moment. The process of reconciliation in South Africa was hard and it took many years, while never been fully completed. Yet, Wolterstorff considered their fight to be just, in contrast to the present fight of populism. Why is that? prison (Strafanstalt) of Basel. This fact is surely important. From 1947 until 1954 Barth’s preaching activities were interrupted. But in 1954 he started preaching again more regularly. However, he restricted himself almost completely to the prison of Basel as his pulpit. These sermons have become famous because of their pastoral nature. The sermon for Christmas Day 1954, about Luke 2,10-11, offers abundant testimony to this quality.

prison (Strafanstalt) of Basel. This fact is surely important. From 1947 until 1954 Barth’s preaching activities were interrupted. But in 1954 he started preaching again more regularly. However, he restricted himself almost completely to the prison of Basel as his pulpit. These sermons have become famous because of their pastoral nature. The sermon for Christmas Day 1954, about Luke 2,10-11, offers abundant testimony to this quality.

: the Rev. Dr. Thomas Henry Louis Parker. He died on Monday April 25th of this year, at the blessed age of 99 years. Parker was an outstanding scholar, both versed in Calvin Studies as well as in Barth Studies. His death has not attracted the same amount of attention as John Webster’s, but I gathered it was mentioned on Facebook, and also on the website of

: the Rev. Dr. Thomas Henry Louis Parker. He died on Monday April 25th of this year, at the blessed age of 99 years. Parker was an outstanding scholar, both versed in Calvin Studies as well as in Barth Studies. His death has not attracted the same amount of attention as John Webster’s, but I gathered it was mentioned on Facebook, and also on the website of

offerings in the OT are memorials before God. It is in that sense we have to think about the Eucharist. As Calvin explains in his comments on Numbers 19: Christ is our Memorial and we offer Christ daily to the Father. And that’s what we do in the Eucharist. We are participants in Christ’s sacrifice.

offerings in the OT are memorials before God. It is in that sense we have to think about the Eucharist. As Calvin explains in his comments on Numbers 19: Christ is our Memorial and we offer Christ daily to the Father. And that’s what we do in the Eucharist. We are participants in Christ’s sacrifice.